The Drifter Is a Gripping Mystery with Grating Characters

Is Mick Carter, protagonist of The Drifter, supposed to be likeable? I finished all nine chapters of the point-and-click mystery adventure over the course of 10 hours, and I’m still not sure. I sure do know that I don’t like him, and that I also had my complaints with several of the game’s other thinly drawn, archetype-based characters—even though I loved the story unfolding around them.

The mystery at the heart of The Drifter kept me in its grip for the game’s entire runtime. It’s well-told and well-paced, aside from the last chapter, which felt a bit rushed. The Drifter’s writers tie up every loose end in a pretty tight bow, for better or worse, and that’s no small feat given how many loose ends unravel over the course of the game’s science-fiction time travel story.

The Drifter starts with protagonist Mick Carter train-hopping on his way to his mother’s funeral. He shares a train car with a fellow drifter who, after an unprovoked altercation, ominously tells Mick he just can’t seem to stay dead. By the end of the game’s first chapter, Mick has been cursed with this same fate: like any good video game protagonist, he comes back to life every time he dies, but he actually remembers it all and is understandably fucked up over the implications. Mick starts speculating that amoral scientists have been experimenting on unhoused people and drifters like himself in order to test this new sci-fi ability, but over the course of trying to prove out his theory, he gets framed for multiple murders and starts actively hallucinating (an apparent side effect of his new inability to die). Mick somehow manages to enlist a handful of other characters to help him solve the mystery of what happened to him: a young female journalist who’s been looking into an epidemic of missing unhoused people, his dismissive psychiatrist sister, and his ex-wife, who hates him (for abandoning her after the death of their teenaged son a few years prior) and yet still clearly carries a torch for him despite it all.

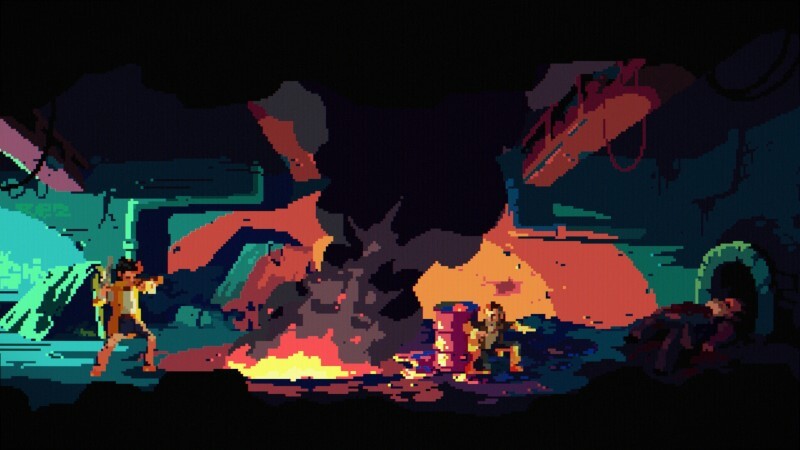

There’s a high level of craft on display in The Drifter, especially considering its small team. It has gorgeous pixel art that’s complemented perfectly by a moody, synth-forward soundtrack; the dead bodies start to stack up very early on in this mystery, but because of the stylized visuals, The Drifter never verges into full-on horror. Stacks of corpses, ghostly hallucinations, and monstrous sci-fi abominations don’t ever look that scary when they’re so pixelated, and the strong story at the center of The Drifter ensured I felt just the right amount of creeped out. The Drifter is also fully voice-acted, with nary a bad performance in the bunch; Adrian Vaughn’s work as Mick truly elevates scenes that would otherwise fall flat.

My few specific problems with the point-and-click puzzle design will be doubtless solved upon the game’s full release, but I’ll explain what happened just in case they’re not. I beat The Drifter in 10 hours, but to be honest, I should have done it in six, if not for a specific setting that wasn’t yet complete in the review build I played. There’s an accessibility mode that gives the player the option to highlight all clickable objects, but unfortunately, only the first chapter had been completed in the build I played. This meant that, from time to time, I ended up getting hopelessly stuck on a puzzle and had to resort to the classic “solution” of slowly swirling my mouse across every single inch of the screen, clicking on as many pixels as possible until I found whatever object I had somehow missed. I only had to resort to this a few times, but every time I did, it sucked. When you play this game, dear reader, turn on that accessibility setting and use it liberally; it should probably be the default in the game, especially because the pixelated art style makes it harder than it otherwise would be to tell what’s interactable.

There were also a couple of puzzle-solving sequences—specifically, Chapter 4—that were not necessarily hard so much as tedious. In the fourth chapter, Mick has to navigate between several different locations downtown, talking to different people at each one, presenting each of them with different clues. It just wasn’t always obvious which character might be capable of weighing in on each clue, so I ended up circling Mick around to every single character every single time I collected any new piece of information, just to try to figure out which of them would help me. Oddly enough, Chapter 7 has a similar structure (Mick explores multiple floors of a large building, with different characters on each floor, each of whom can interact with different clues), but stronger writing in that chapter made it a lot easier for me to figure out what Mick should do with each clue. My only problem in that chapter was not realizing I needed to give a character a food ticket for a bowl of soup instead of a bowl of soup, which is going to sound like a non sequitur but which I’m just going to include here because I want to save other people from spending 20 minutes of their damn life trying to figure out how to proceed with that quandary.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-