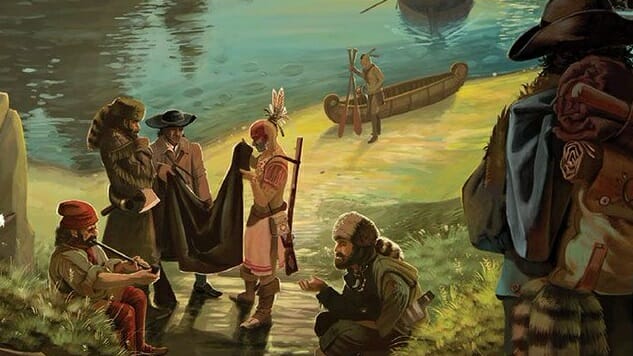

Century: A New World Is a Frustratingly Complex Board Game

Emerson Matsuuchi’s trilogy of Century games, which began with 2017’s Century: Spice Road and continued with last year’s Century: Eastern Wonders, has now concluded with the brand-new Century: A New World, with each of the three games sharing one common mechanic and with rules that allow you to play any of the games on their own or in any combination of two or even all three. Each game offers a different twist on that common mechanic, but while Spice Road was elegant (and Splendor-like) in its simplicity, and Eastern Wonders ratcheted up the level of difficulty without becoming cumbersome, A New World might go a shade too far in its complexity.

All three games revolve around four trade goods, represented by yellow, red, green, and brown cubes, with increasing values (I listed them from lowest to highest), and in every one of the games you take some series of actions to upgrade whatever cubes you have to collect a set that you can trade in for an objective card that is worth some fixed number of victory points. In Spice Road, the entire game revolves around cards: it’s a basic hand management game, where you collect cards that allow for specific upgrades, trying to create a little engine of cards that you can run through over a series of turns, then “resting” for a turn to pick your played cards back up so you can do it all over again. In Eastern Wonders, you move around a map of hex tiles, each of which offered a specific upgrade action, but the game adds two layers: everyone plays on the same map, so you can end up blocked out of certain actions; and you can gain bonuses by visiting more tiles and building more of your trade stations. Both games play in 30-45 minutes, and turns are usually fairly quick.

A New World still has the four cubes and the core concept of upgrading your goods to buy victory point cards, but it does so in a worker placement game that adds at least four distinct new mechanics to the game. You start with six meeples—if you have young children or cats, be warned these meeples are very small—and can add more over the course of the game by buying certain cards, a bit reminiscent of Stone Age (sorry, there’s no “love shack” here). Only about half of the board is playable when the game starts; certain point cards also let the player who wins them remove an exploration tile from the board for some very modest bonus, which also opens up a new space for players to use. There’s a set collection mechanism, where each player can earn up to three bonus tiles that reward you for collecting cards with certain symbols on them—for example, you can get three points for every pair of cards where one shows a hammer and another bears a dreamcatcher. You may have to skip an occasional turn to retrieve all of your meeples from the board, but you may get one or more meeples back from other players’ moves; if someone wants to occupy the space you’re on, they can bump you by playing one more meeple than you have on that tile. The point cards also can give you certain bonus abilities, like gaining an extra cube on certain tiles, or allowing you to go to certain tiles with one fewer meeple (merson?) than the tile ordinarily requires.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-