Board Game It’s a Wonderful Kingdom Can’t Match Up to It’s a Wonderful World

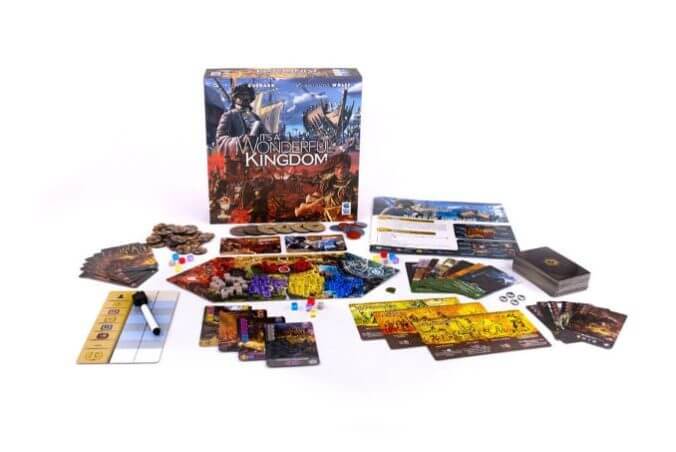

It’s a Wonderful World came out in 2019 and, at least to my knowledge, got lost in the pandemic’s first year, only breaking out in 2021 as conventions ramped back up and people were playing more games together. It’s crept all the way up into the top 150 on Board Game Geek’s user-generated rankings of every game, like, ever, and keeps rising. One of the few criticisms of the game is that there’s almost no player interaction—the sort of game derided as “competitive solitaire”—so the designer brought out a new version, It’s a Wonderful Kingdom, late in 2022, which is for either two players or as a solo game, and in two-player mode, you are definitely fighting your opponent. I think it loses some of what makes the original game so good, unfortunately.

It’s a Wonderful World is sort of a mashup of Race for the Galaxy and 7 Wonders, with a little more resource management involved. Each player gets a unique start card that provides a few resource cubes at the start of every round and a game-end points bonus based on what you’ve built. In each round, you receive a hand of seven cards, pick one to keep, and pass the remainder to your neighbor (what’s known as “card drafting”). You get a new hand from your neighbor on the other side, pick a card, and pass the rest. Once all cards have been selected by players, then you move to the next phase, where you decide which cards to build and which to ‘recycle’ for resources. Building cards requires two to eight resource cubes, with five different colors of such resources. Some cards produce resources in future rounds when you build them, and some are worth victory points at game end. Some do both. All cards are worth a single cube of a specific color if you recycle them. So in each round, you try to align your production and recycling with your building needs to get the highest possible score at the end of four rounds. There’s only one way in which you compete directly with your opponents before the final scoring, as there’s a small bonus after each round for the player who produces the most of each of the five main resource types.

There are two catches with resource production in both of these games. One is that you can’t save resources from round to round—if you produce something, or get it via recycling, you have to put it on a building that needs it, or else you send it to the “empire,” where it sits, taunting you, until you collect five cubes there and get a red wild cube instead. The other is that production is sequential, with each color producing in a set order, so you might get enough cubes of one color to finish a card that produces cubes of another color, and then be able to use that card in the same round.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-