Naishi Is a Good Card Game with a Deeply Misguided Theme

Naishi looks like another capture-the-flag two-player game when it’s set up, but don’t be fooled: it’s a tight tableau-builder where you’re just fighting to draft cards from the center row as you each try to get the most valuable set of ten cards, with only half of them visible to your opponent. It’s a solid game that shows some clear effort by the designers to keep it balanced even with some wide variance in how the cards score, but it’s held back by a theme that not only doesn’t fit the mechanics but continues a bad trend in the hobby.

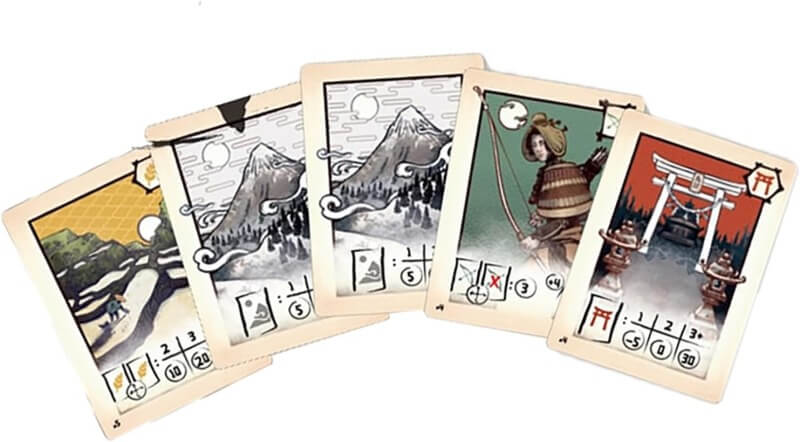

In Naishi, you start with 10 mountain cards, five in your hand and five in your “line.” On your turn, you select one card from either your hand or line, discard it, and then take the card in the same position in the center row to replace it, playing that card face-up. If it goes into your line, it remains visible to your opponent, but if it’s in your hand, it’s hidden. You may also use one of your emissary tokens to take a bonus action, swapping the positions of two cards in your tableau, doing the same with two cards in the center, or discarding the top cards from two central piles. Or you may use the permanent emissary action that is available just once per game—if one player uses it, they lose that emissary token for the rest of the game, and the other player can’t use the action—which allows them to swap a card from their tableau with the card in the mirrored position in the opponent’s tableau. That’s the only way you can ever take a card from your opponent in Naishi.

The game ends when two of the center row’s draw piles are empty, or if one pile is empty and one player declares the end of the game, after which the other player gets a final turn.

There are 12 card types in Naishi, including mountains, and they each score differently. Mountains are the starting cards; if you have two or more left when the game ends, you lose five points, but if you have exactly one left, you get five points. The other card types score based on their positions, on what cards are adjacent, on how many different card types you have, or in other ways. There’s also a Ninja card, which has no inherent value, but at game-end if you have a Ninja in your tableau, you can pick another character card (not a place card) you have and treat the Ninja as a copy.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-