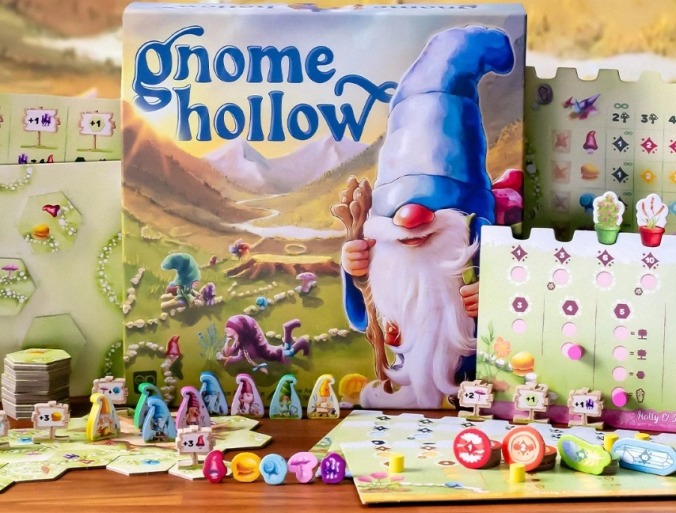

Forge Your Own Path in the Board Game Gnome Hollow

Gnomes are annoying little creatures, what with their “collecting” mushrooms and flowers that aren’t theirs and messing with each other’s carefully laid pathways. The 2024 game Gnome Hollow gives each player two gnomes to move around the garden and the markets to try to create completed paths to gather those items for scoring—but another player can lay tiles that help them and make it harder for you, one of the ways this game takes some typically solo pursuits and infuses more player interaction.

Gnome Hollow is the first game from designer Ammon Anderson, whose second game, Twinkle Twinkle, will be out early in 2025. This game is ultimately about tile-laying and set collection, as on every turn you have to place two tiles, either from the market or from your personal supply if you have any there, and then move one of your two gnome meeples to any of four areas so you can claim something of value.

The core of the game is laying those hexagonal tiles to build paths. Once you’ve completed a path that crosses at least three tiles, you can claim it if your gnome is already somewhere on it or if there are no gnomes on it, taking one mushroom per matching symbol on the path itself, saving those to sell at the market. You take one of your eight ring markers from your board and move it to any available space under the number of tiles in the path; paths of five to seven tiles get you significant bonuses, including letting you place two markers at once, while paths of three to four tiles don’t get you anything extra. Then you move one of your two gnomes to a new location—to another path to claim it, to the mushroom market, to a signpost to get a bonus, or to the flower fields to get another flower for end-game scoring.

Play continues until one player has placed all eight of their ring markers, after which each player gets one more gnome action (but doesn’t get to place more tiles), and then you score. During the game, you can trade in sets of two or more mushrooms of a type for points, with rarer mushrooms worth more points for bigger sets. Each mushroom type has its own row with spaces for specific numbers of mushrooms in the set, with sets of three or more blocked once a player has turned in a set of that number of mushrooms of that type. So the first player to turn in a set of four purple mushrooms places a marker on the four box in the purple row, and no other player can claim it—they can turn in three mushrooms, or turn in five, but even if they have four mushrooms they can only take the bonus for three.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-