The Games Behind the Bans: Vile: Exhumed and Girls Purgatoriem

It has been quite a couple of months for independent games. Both Steam and Itch have wiped games from their libraries, due to payment processor pressure. It might be gauche to say, but it is true that bans garner their subjects attention. I might never have heard of Girls Purgatoriem if itch.io had not excised it from its library. But it also makes it harder to approach these works on their own terms. Vile: Exhumed will be forever associated with its banning. Critics, journalists, and fans will discuss its removal from Steam in greater depth than the game itself. What could have been an interesting work on its own terms is now the tip of a spear in yet another culture war.

I wanted to write this as something of a corrective against that. I can only go so far. I am still highlighting these games because of what happened to them. However, excepting this intro and a couple asides, I want to focus on these games as aesthetic objects, to treat as I would if I were writing a regular piece about them.

Without further ado, let’s get analyzing.

Vile: Exhumed Puts You in the Skull of a Killer

I want to get this out of the way first. The fact that Valve barred Vile: Exhumed from sale on Steam is absurd. For one, the game is directly critical of “male entitlement,” keen-eyed about the mundane things that enable men to hurt and kill women. For another, it violates Steam’s guidelines only if you take an especially punitive and misunderstanding eye to it. Vile‘s banning underlines the impracticality of these measures. Who exactly are these bans protecting? Who are they targeting?

Spoilers follow:

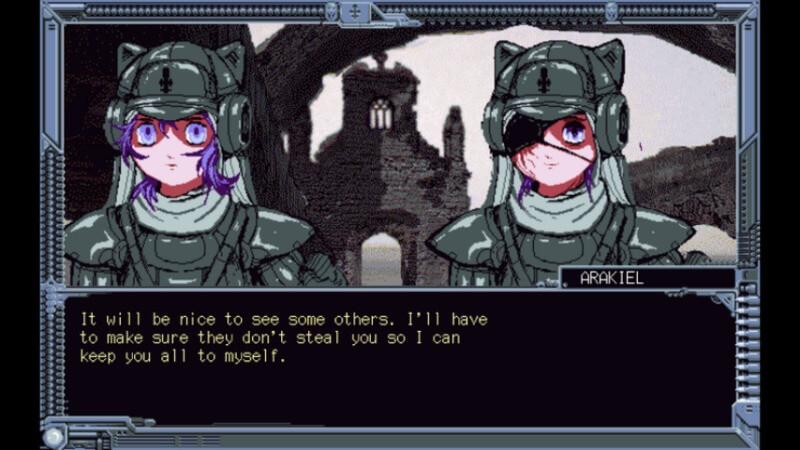

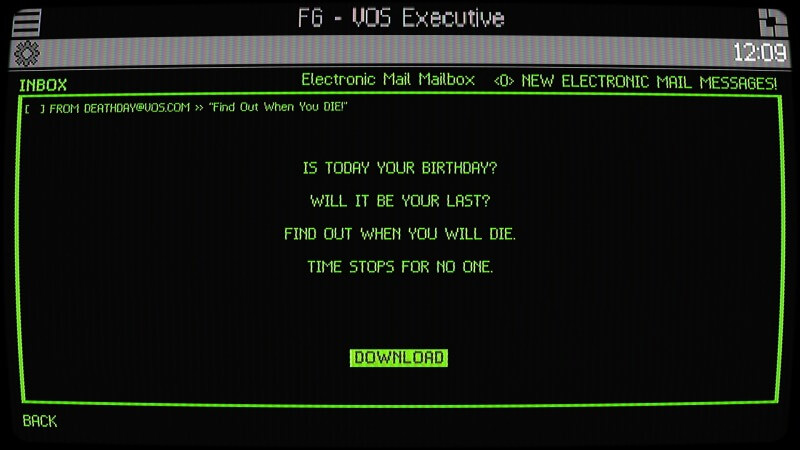

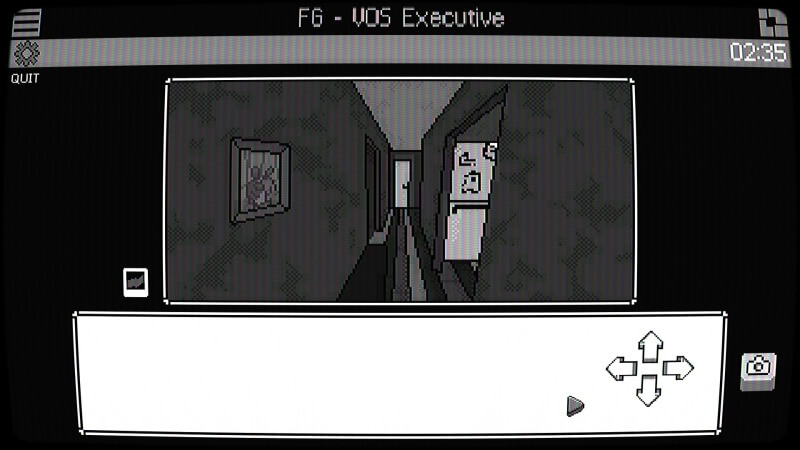

Vile: Exhumed’s most interesting element is its queasy sense of (dis)identification. In it, you explore the PC of one Shawn Gerighs, a horror and porn enthusiast. But the deeper you go into his files and programs, the more it becomes obvious that he is stalking and murdering women. It also becomes clear that, in the game’s own parlance, you are him.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-