Six Missing Children Have Haunted These Arcade Cabinets For Decades. Why?

Five days ago—on October 26, 2025—Reddit user pablo_187 posted a photo on r/creepygaming.

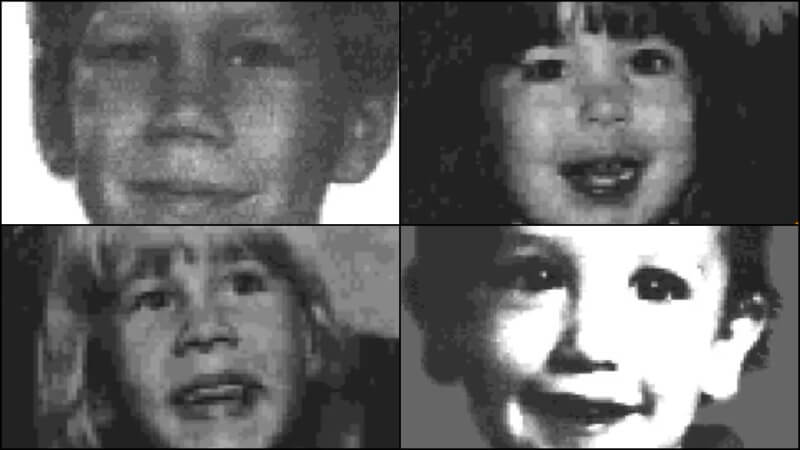

The photo shows the front of a faded, well-played cabinet of Sente’s 1985 Mini Golf. On the screen are the monochrome photos of two young boys: Taj Allen Merriman and Steven Phillip Curtis. Below each, in red text, is their date of birth, information about their appearance, and when they were last seen. Between each, a logo—the acronym “VOCAL” under an arched Hide & Seek Foundation, Inc.

These are missing posters.

The Reddit user wrote, “I saw a post which was the same thing I found. I was at Cidercade and saw an abduction alert on one of the arcade games. Another guy found the same thing on the same game.”

Though disturbing, this is not a unique discovery. This post is actually one of several made about this missing screen to Reddit since at least 2020—including another on r/CreepyGaming. An r/pics post from five years prior shows the same screen, albeit from a different Sente Mini Golf cabinet in Greenville, SC. Cidercade—the arcade mentioned by pablo_187—is a Texas-based chain. The cabinets have been found throughout America over the last several decades, waiting to unsettle unsuspecting patrons.

This isn’t limited to specific cabinets, either. When played in MAME, Mini Golf reveals DIP switch options for the missing children in the ROM itself. Right below “Service Mode” and “Add-A-Coin” are three unique options: “Display Kids,” “Kid On Left Located,” “Kid On Right Located.” These posters are coded in the very game itself.

What makes this more interesting is that Mini Golf is not the only Sente cabinet with these missing posters. Both Stompin’ and Gimme A Break also feature them. Discussions about these screens date back over a decade, earlier than any Reddit thread. The earliest I can find is an Atari Age discussion from 2013.

“Years ago, I remember seeing a Mini Golf arcade game in a gas station near me,” wrote ThunderFist on September 21, 2013. “I wasn’t able to play it, but I remember watching the demo and seeing the screen with the two missing boys pop up […] I always wondered what became of the two boys shows in Mini Golf and recently decided to look into the cases. Downloading and playing set 2 of Mini Golf in MAME, I took a screenshot of that particular screen and took down information on the two boys.”

Here’s where the story took its first turn, in a follow-up comment from RetroRussell on July 2, 2019, almost 6 years later.

“I just got working on making a video for Mini Golf and I found a different pair of missing kids, girls named Malinda Marie Smith and April Rose Yates.” he wrote.

A 2017 Arcade Museum post reveals two more photos of missing boys—Daniel Godfrey Owens and Charles Brandon Morris—for a total of six known missing posters in Sente arcade games. These appear to be the only six photographs, based on my own and others experiences; however, it’s possible there are more. How these photos ended up in these specific games—as well as the parties involved to make it happen—remain a mystery to most.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-