Inside The Cancelled Bonk Game: How Hudson’s Ice Age Froze A Cult Mascot’s 3D Debut

Bonked.

Inside the origins of Hudson Soft’s Cro-Magnon cutie, his rise to multi-platform fame, and how his seventh generation console debut was cut short by mergers and acquisitions.

Your average list of beloved ‘90s platformer icons will, without doubt, name-check Mario, Sonic, and Crash Bandicoot. One deserving name, however, may not make the cut: Bonk.

One potential reason? The pint-sized cave boy doesn’t have a unified moniker, as “Bonk” is just a Westernized version of the tyke’s name. In Japanese, he’s known as “PC Genjin” (sometimes spelled as “PC Gengin”)—that’s “PC Caveman.” Created by Kobuta Aoki—also known for his contributions to the first Croc—the bald baby boy debuted in Gekkan PC Engine, the official companion magazine for the console known as the TurboGrafx-16 in North America.

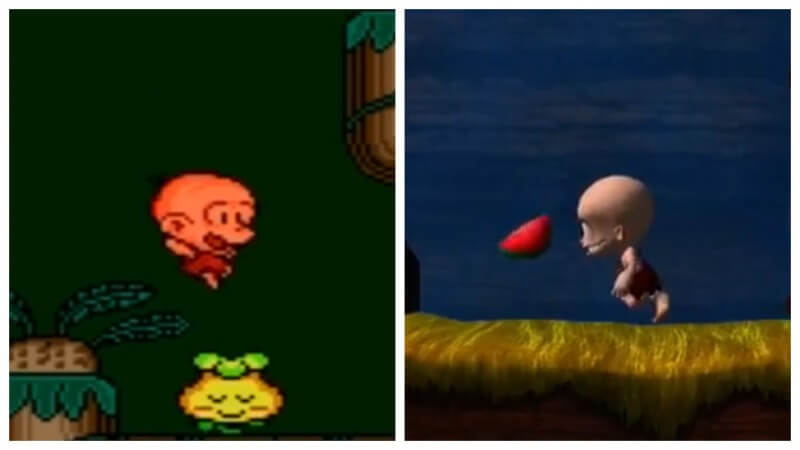

July 28, 2025, marked exactly 30 years since the release of Super Genjin 2—the last original console title in the series. Both this game and a later 3D remake of Bonk’s Adventure for PlayStation 2 and GameCube would remain in Japan, where—after a few asset flip puzzle game spin-offs—the series would go dormant entirely after 2008.

17 years later, this was the last time most of the gaming public heard of Bonk.

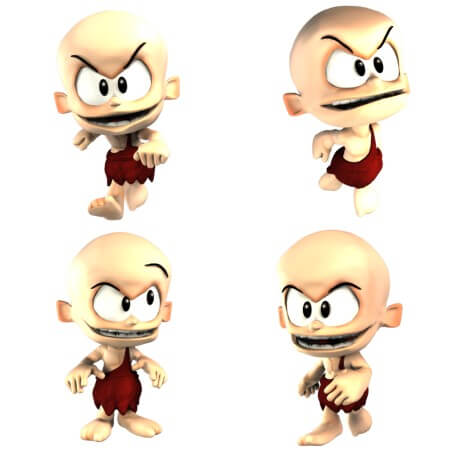

However, it wasn’t always going to be this way. Bonk almost made the leap to 3D with an all-new game in 2011. Unfortunately, Konami—and the planet itself—had other plans. This is the story of Bonk, his PC Engine origins, and the team who raced against a ticking clock and dwindling budget to bring him back to life for modern audiences.

In The Beginning…

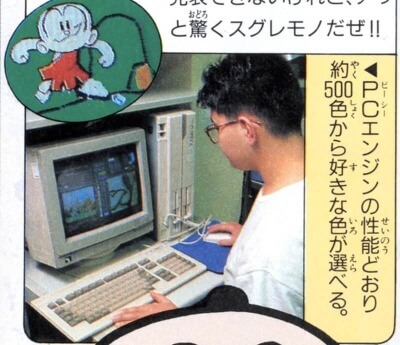

Bonk wasn’t the first PC Engine mascot. That would be the somewhat horrifying PC-Engineman, who lands somewhere between a luchador and unfortunate caricature. The cave-child wouldn’t arrive until Gekkan PC Engine’s sixth issue in March 1989, though his appearance was teased at the end of the prior issue. Aoki’s comics—which were drawn on a computer monitor, then photographed and scanned into the magazine—were simple and cute four-panel gags which centered on Bonk and an assortment of dinosaur pals.

Hudson officially stated that readers were enthusiastic enough about these comics that a game was quickly put into production. As per the Bonk Compendium:

The new character […] was a hit. Popularity of the comic increased to the point that Hudson Soft and Red decided to make a game based on the character, which would serve as the system’s mascot. […] The project was accelerated to the point that Atlus only had three months to develop the game and thus employees performed many late night and marathon weekend coding sessions.

Bonk’s Adventure, however, is better than these circumstances would lead one to believe. The first game is a colorful, imaginative title with expressive animation and memorable character designs. It’s challenging, but not tough as nails, and straightforward enough to clear in a single sitting. In other words, it’s the perfect game to sell a console to children. At the time it was well-received, netting year-end “best of” awards from publications such as Electronic Gaming Monthly and OMNI Magazine.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-