The Board Game Gatsby Doesn’t Understand What Makes Fitzgerald’s Novel Great

Whoa boy, do I have a lot of feelings on Gatsby, the new two-player game from Bruno Cathala and Ludovic Maublanc, good and less-good. The game itself is pretty solid, although there are some balance questions near game-end, as players play take-that across three different mini-games with lots of bonuses across them. The title is just weird, as the theme has absolutely nothing to do with The Great Gatsby, or F. Scott Fitzgerald, other than some Jazz Age imagery.

Gatsby is a specific style of two-player game I’ve always thought of as a “fuck-you” game, because just about everything you do is aimed directly at your opponent, and will either come across as you trying to fuck your opponent over, or will make them want to say “fuck you” for the move you just made. Jaipur, still my all-time favorite two-player game, is very much one of these. Zenith, which I reviewed in June and might be my favorite new game of 2025, is another.

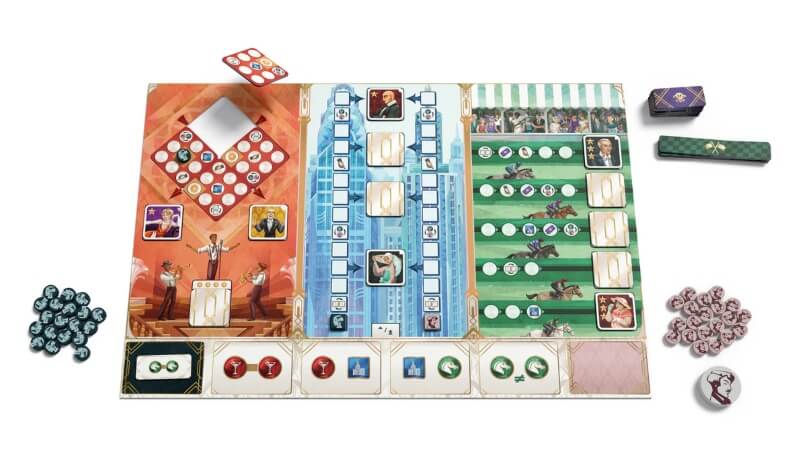

In Gatsby, there are three boards, representing the cabaret (red), finance (blue), and the racetracks (green), and players will place tokens on the red and green boards or move their single token up the blue board to hit new bonuses and push to claim some of the game’s character tiles. Those tiles come in five background colors, and there are three of each in the game, although there are only 12 of them out in any single play. You win if you get three character tiles of the same color, or one of each of the five colors; or, if all characters are claimed from one of the three boards, then players add up the stars on the character tiles they’ve claimed, and the player with the most stars wins. When the game begins, half of the tiles are face-up and half face-down; the latter are never revealed even when a player claims one.

One of the big constraints in Gatsby is in how you take your turn: There are four basic move options, and you can’t take the same move that your opponent just took. One is to place two of your tokens on the red board, adjacent to any tokens already there and then next to each other. Another is to place one token on the red board and move your marker up the blue board. A third is to move your marker up the blue board and place one of your tokens on any of the five green racetracks that isn’t completed. And the fourth is to place two of your tokens on the green board on two separate tracks.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-