Best of the Rest: Cult Classic and Misshapen RPGs to Learn and Love

Ask just about any game fan who lived through the ’90s for their top five RPGs of the decade and odds are Final Fantasy VI and Chrono Trigger will battle for supremacy near the top spot. Some will extend their vision into the back end of the decade with the Playstation finally finding its footing after a questionable start with Camelot’s Beyond the Beyond, while fewer still will call up some classics from Sega’s wonderful misfire, the Saturn. Undoubtedly, some nerd will tell you Live a Live, despite not having played it until a couple of years ago (they’re not wrong though). But we have, if not a proper canon, at least the strong entrenchment of a hierarchy of big budget bangers—the RPGs that established a vanguard and set the tone for Final Fantasy VII to blow the doors off the genre and let everyone feel like an RPG nerd. What about the cult classic RPGs, though?

For every Secret of Mana and Pokémon Yellow there’s another game waiting in the wings. A Kemco also-ran. A Game Arts diamond in the rough. Telnet’s laudable effort. A true cult classic RPG, one that doesn’t have a lot of fans, but whose fans that do exist are ride-or-die. This list is dedicated to some of the best of the rest—classics in their own minds, lesser loved entries in their bolder franchises, the beloved-by-few-and-unknown-to-most games that make up the second runners of the 16-bit era.

We have a lot of ground to cover, so let’s get started…

Paladin’s Quest (1992)

Developed by all-but-unknown Copya System (who otherwise gave us Air Diver, Lock-On, and Dead Heat Scramble for the Game Boy) and released in Japan under the much more accurate and descriptive title Lennus: Memories of an Ancient Machine, Paladin’s Quest didn’t review well, and I honestly don’t remember a single other person who owned or rented it at the time.

There is no paladin in Paladin’s Quest, and the box art is notably nondescript, making it the first of two games undercut by Enix’s questionable localization decisions on this list. But perhaps that’s only fitting for a game based entirely around questionable decisions.

The story at the heart of Paladin’s Quest is that of a young lad who gets goaded into unleashing a cataclysmic evil from inside an ancient machine called Dal Gren. (Growing up only an hour from the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division made this unintentionally hilarious as a child). After the big evil kills all of his classmates and obliterates the Magic School he was studying to become a great Spiritualist at, he’s told that all this is going according to prophecy and that he has to stop it and save the world. Also there’s an evil Dictator who wants to use the power of Dal Gren to enslave the world, etc. Chezni (yes, that’s the hero’s name) has to collect a bunch of elemental powers from all over the world, aided by a Girl and some randos, and become the ultimate Spiritualist to stop Dal Gren, the big Evil, and Zaygos the Dictator.

To top it off, the game looked old by the time it came out. Two years after Final Fantasy IV and mere months after Secret of Mana, it had a bog standard story and Master System graphics. It really didn’t stand a chance with gamers or reviewers at the time.

Yet, for as much tracing other RPGs as Copya System did, they also truly dared to try things. Say what you will about the bright pastel landscapes that fully extend into the dungeons, but the violent misunderstanding of Moebius gave us some alien and evocative tile sets. The decision to make magic pull from health instead of having a discreet magic pool was inspired for a game putting emphasis on the personal relationship to magic (even if the healing system was a confusing mess, and spellpower only increased through frequent casting). Instead of a fixed party (some guests will float in from time to time), a series of hirable mercenaries that came with their own, inflexible equipment and ability load-outs rounded out the final two slots leading to the tension of hiring newer, more advanced mercs when they became available, or keeping your now-leveled up henchmen. Sure, there’s no Palom and Porom anywhere here, and your killers for hire never seem numerically up to the challenge, but whether you’re stuck in 1992 or picking it up in 2025, the vision of a choose-your-own-weirdos game with fantasy Task Rabbits like FastJo, MeanMa, or the Rasav brothers is palpable.

It’s hard to actually praise Paladin’s Quest without feeling like you’re doing it ironically. But you’ll just have to trust me that while deeply frustrating and flawed, and absolutely outshined by the first three Phantasy Star games that came out years ahead of it, there’s something here beyond just another impeccable Kohei Tanaka (Gunbuster, Alundra) soundtrack.

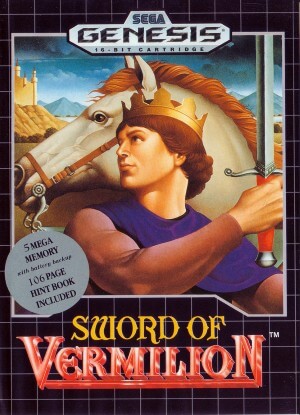

Sword of Vermilion (1989)

I hold fast that the Yamaha YM2612 FM synthesis processor inside the Sega Genesis was actually the superior sound chip for RPGs, and while Sword of Vermilion‘s soundtrack gets nudged out by the sheer volume of incredible compositions of the ’80s and ’90s in a pure head-to-head, it’s those filthy-but-clinical jams that push this middling multi-modal experiment from its strangely Britannic riff on Xanadu and Phantasy Star to a next-gen vibefest.

If it wasn’t for an abruptly aborted sleepover at Conduct Disorder Ben’s house, I probably would have continued to walk past the (again) strangely Britannic box art for Sword of Vermilion. But before he decided to go outside and get a clump of dirt and rocks to throw at me out of nowhere in the living room, I really enjoyed my time watching him play Sword of Vermillion for like three hours. Maybe I’d like to do that myself, I thought.

Pull apart Sword of Vermilion and it unravels quickly. Its third-person perspective town navigation is a grim and generic affair of vague, European-style towns and white-on-blue menu conversations and commerce. Stepping outside of town leads to the kind of split screen PC-88 vision one might expect from Japanese-made RPGs in this era (albeit with a decidedly less impressive UI). Gone are the bespoke animations of corridor traversal that were a highlight of the Master System’s Phantasy Star, replaced by the almost beautifully brusque pop-up book rendering you expect from Space Harrier and Outrun home ports (this is a Yu Suzuki production after all). For the random encounters, we borrow directly from Xanadu. Isometric arenas filled with an assortment of baddies with button-mashing sword swings mixed with the occasional burst of magical abilities to keep things interesting. Boss fights take an entirely different approach, zooming in for a side-scrolling arcade beat ’em up mode.

It’s a far cry from the forward-thinking, genre-defying, seismic gaming shift that Yu Suzuki would present the world with in the production of Shenmue (also, definitely an RPG, don’t fight me, I’ll win). But you can see the minds behind it hard at work, even if it doesn’t gel in quite the way you’d want.

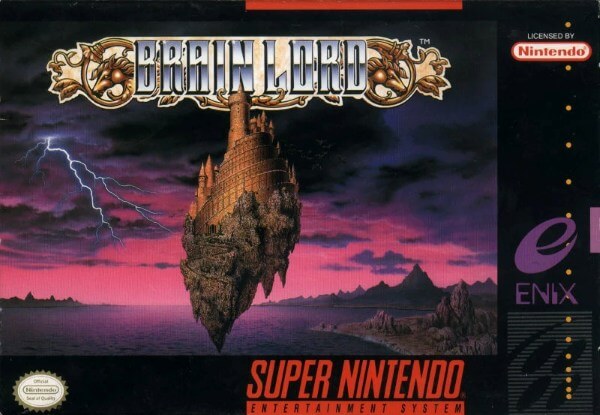

Brain Lord (1994)

I can’t tell you the number of weeks I walked right past this game at Blockbuster. “Brain Lord” what the hell? Get real. I’m not playing a game called Brain Lord. And I’m sure, you’re also looking at this list going “Dia, please. It’s called Brain Lord, AND it looks mid.”

It does. It looks mid. And, if we’re honest, it is mid. In a world of 7/10 Ys-likes daring to reach for the brass ring, this one says “I’m happy just being a 5.” But what if I told you this game’s strangely bulky hero not only got a sword (with an absurd cleave range), but also a bow, an axe, a mace, and a boomerang? All as primary weapons. Plus magic. And nine different familiars that function much like the ones in Symphony of the Night (they float around and basically cast magic).

A bevy of not-entirely-memorable-but-more-than-you’d-expect travelling companion NPCs show up to provide color commentary, advice, and comic relief in both town and dungeon. But they’ll never actually join your party. It’s Brain Lord, not Brain Team.

But why Brain Lord? Because MILORD, you’re going to need to use your BRAIN. This game is full of puzzles. Really hard involved ones. There’s only five sprawling dungeons, but each one coughs up more puzzles than your high school DM could for an entire BECMI campaign. If you liked Void Stranger but wanted more ARPG out of it, Brain Lord is exactly what you’re looking for, and a true cult classic.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-