Catherine

(Multi-Platform)

If you haven’t been playing close attention, you’d be forgiven for thinking of Atlus’ Catherine as “that sex game,” or something like that. Pre-release marketing focused on the blond curl and apple blush, the stocking hems and saucy liquor-sips of the title character—bet you thought I’d say “titular,” right? Yeah, no. The hook for Catherine wasn’t just its lissome leading lady, but the idea that she was the avatar for a mature game. A game about a man’s sex life; a game for adults.

Catherine does explore mature themes, but not necessarily the ones you’d guess at from early imagery of its protagonist, shaggy-headed, sleepy-eyed thirty-something Vincent, surrendering slack-jawed to the deer-legged physical approach of the young lady. The issue is that Vincent has a longtime girlfriend, Katherine (yes, with a K), and she’s not so subtly begun indicating that she’s ready for marriage.

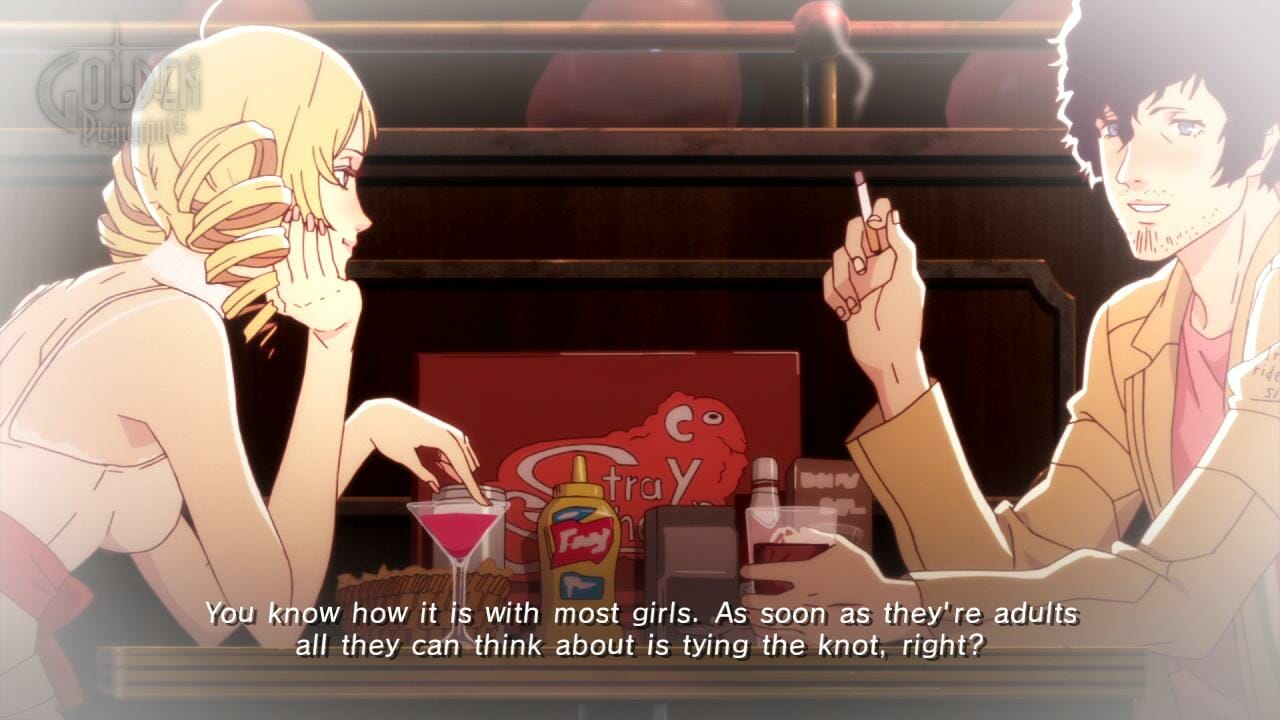

Vincent, on the other hand, wonders why he and Katherine can’t just continue on as they have been. Right off the bat, the game’s story, established through eloquent animations from popular Studio 4?C, shows the man as something of a classic slacker without much upward mobility. He lives in a dingy little studio apartment, seems disinterested in his work as some kind of code monkey, and spends every night in the Stray Sheep bar with his guy friends.

Into his indecision in the face of Katherine’s pressure comes vivacious 22-year old Catherine, who finds Vincent as he’s drinking off his stress—and beside whom he wakes up the next morning, with no specific recollection of having crossed the line of no return into infidelity. As Catherine becomes an increasingly complex problem for Vincent, the town in which he lives is plagued by rumors of a “witch’s curse” that kills cheaters in their sleep.

The nightmares that Vincent begins having at the game’s outset are its primary gameplay mechanic. Cast into a strange underworld, Vincent and a literal flock of other men (all of whom look like horned sheep to him) are tasked by a strange voice with climbing towers of blocks. Pushing and pulling these to create a path for Vincent to climb under pressure of time is the player’s task. As the game progresses, the puzzles introduce different blocks with different properties that make the puzzling more complex.

By day, the player guides Vincent through his increasingly stressful life: Taut coffee conversation with Katherine, inevitable rendezvous with the irresistible Catherine, and his nightly visits to the Stray Sheep with his friends. In the bar, Vincent can talk to them and to everyone in the bar, discussing his predicament and learning of others’ views on love as well as their troubles—later it becomes clear that many of Vincent’s fellow sheep in the nightmare world are other bar patrons by day.

In this way, the game polarizes itself fairly cleanly between the challenging block puzzle gameplay of the nightmares and the slower dialogue-driven interactions of Vincent’s waking life. It’s something of a risky choice for the game’s designers to have made, as in general it’s unexpected to find overlap between the type of player who’d be engaged with the former and the one who likes the latter. The game offers a challenge mode for those players who just want to test themselves with the block towers, but no solution for the fan who wants to enjoy the dialog choices and story.

It doesn’t help that the nightmares are actually quite difficult. When the game released first in Japan, popular demand led Atlus to release a patch that would make it easier. Now in its U.S. release, even the easiest mode is still quite challenging, often demanding arcade-style reflexes, memorization and dogged repetition to pass the later levels. Plenty will find it prohibitive. But since the puzzles aren’t random and strategy can be earned and learned, frustration is often temporary.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-