Despelote Understands the Culture and Community of Sports

There have been countless videogames about sports over the decades, but can you think of any about sports as a concept? Not about recreating a specific sport like baseball or football, but about the larger cultural context in which sports exist, and the role they play in society? I’m asking because, hey, I can’t, and I’ve been playing these videogame things since they could only deliver the vaguest, most abstract approximation of any real-life sport. Or I should say I couldn’t, not until the last week or so—not until I played Despelote.

Despelote, a short new work by the Ecuadorian developers Julián Cordero and Sebastián Valbuena, is a game about football (or what Americans still generally call soccer). It’s not a football game, though. It does include a playable recreation of a ‘90s-style football videogame, but you won’t spend much time playing it. Despelote isn’t interested in football as a sport but as a cultural touchstone, as something that brings people, communities, and entire countries together, and how our shared experiences with sports, and our memories of them, continue to impact us throughout our lives.

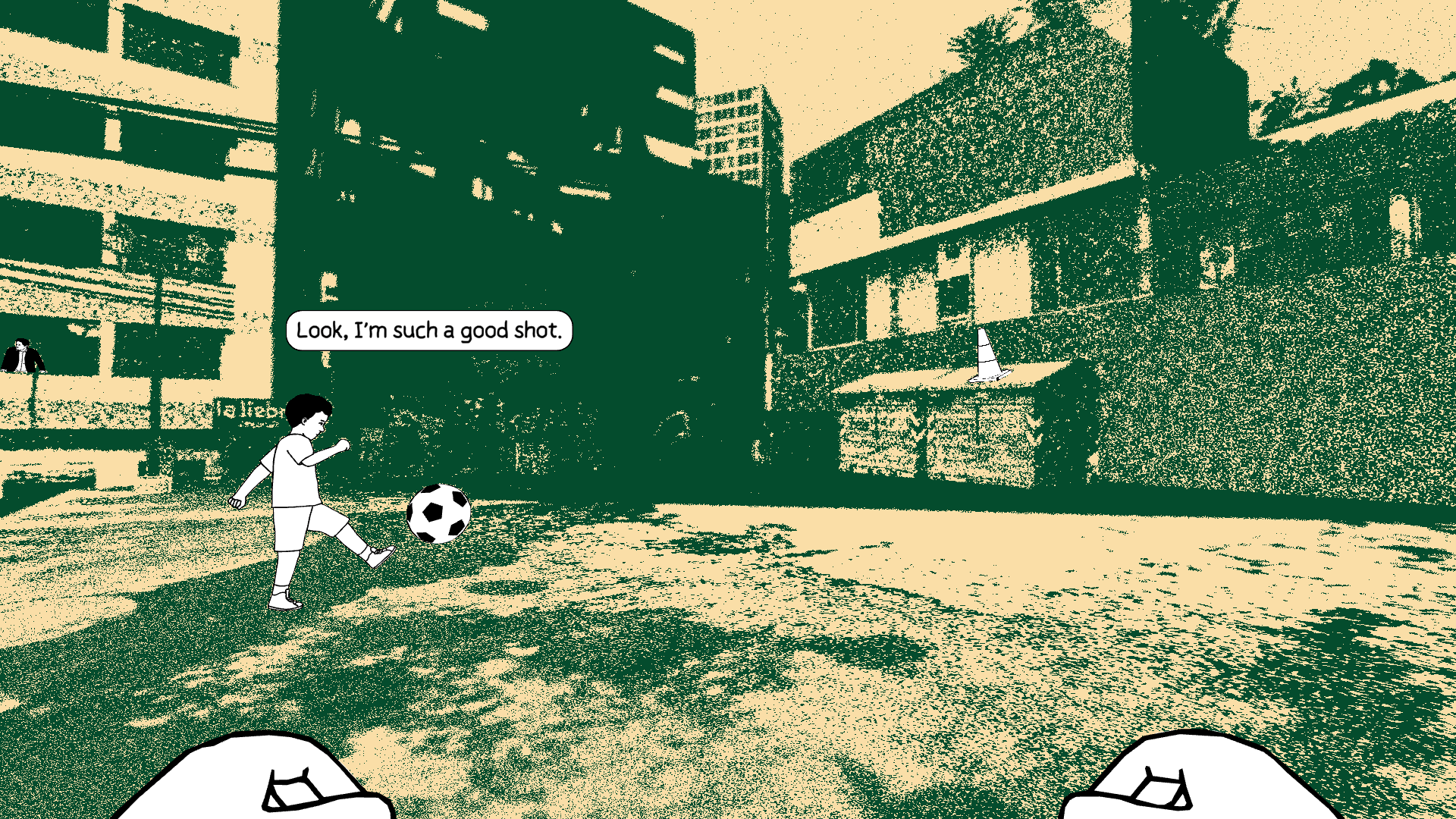

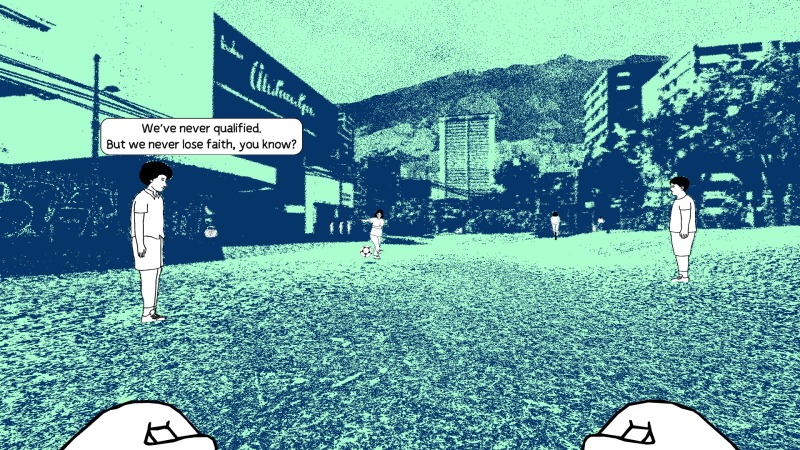

To accomplish this Cordero and Valbuena focus on a pivotal year for Ecuador’s national football team. Some of Cordero’s earliest memories involve Ecuador qualifying for its first World Cup in 2001. Their run to the 2002 games takes up most of the foreground in Despelote, as a football-obsessed 8-year-old Julián turns anything he can get his feet on into a makeshift soccer ball. He and his friends kick around glass bottles, VHS tapes, even actual balls when they can get one, and when they aren’t doing that or playing Tino Tini’s Soccer ‘99 they’re dreaming about football in geography class. On game days, when Ecuador’s facing a South American rival with a World Cup slot in the balance, every TV and radio in town is tuned into the game; it becomes a point of consternation within Julián’s family when one game coincides with a wedding. Other stories about Ecuador and its culture are able to penetrate Julián’s consciousness—there’s a banking crisis related to the country adopting the American dollar as its currency, leading to financial instability and protests, and Ecuador’s struggles to fund and support its own arts and culture is a constant undercurrent in the form of conversations between Julián’s parents, who in real life are an acclaimed director and producer of films—but football is always number one, encompassing everything else happening in Julián’s world. The sound of the protests is identical to the sound of football fans massing on game day, each one a distant, monolithic roar echoing from somewhere else in town, unseen but always heard.

For those crowds, Ecuador’s unlikely run to the World Cup isn’t just a source of pride, but a unifier, and a boost to the country’s sense of national identity at a time of turmoil. Despelote taps into how sports can forge instant bonds between strangers—how if you see somebody wearing your team’s colors, whether it’s the Georgia Bulldogs or Atlanta’s pro teams for me, or the Ecuadorian national team for Julián and his friends and family, you know you have a shared passion and something you can connect over. And given the explicitly nationalistic nature of the World Cup, Despelote looks at a particularly powerful version of this phenomenon—one that Americans like me, spoiled by our routine Olympics dominance and marked by a general lack of passion for any other kind of international sports, can’t fully understand or relate to. (Really, I think the closest American sports gets to the passion of international soccer is college football, but I’m a Southerner who went to an SEC school, so of course I’m going to think that; it’s hard to imagine how much stronger and more personal that kind of loyalty would feel if it wasn’t to some bureaucratic institution I went into debt in order to stay drunk at for four years, but the land I and all my loved ones come from.)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-