Don’t Let an Algorithm Pick Your Next Game For You

When searching for a new game to play, one of the most straightforward ways to determine whether you may be interested in a given title is by looking at its genre. The interactive nature of the video game medium makes gameplay experiences drastically different across genres; if, for instance, you really appreciate the meditative quality of a strategy game, you’ll be hard-pressed to find that specific emotional experience in, say, a platformer. All that said, we’re engaging with art here, not shopping for groceries, and the gaming industry’s severe overemphasis on genre serves to harm players and developers alike.

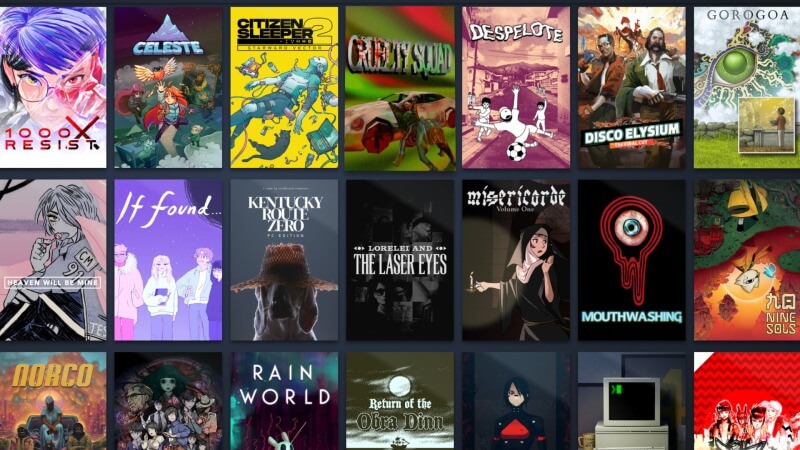

While categorization is a useful shorthand for conveying a title’s gameplay, genre fixation has led to many experiences being reduced to their core mechanics, particularly in the small-budget games space (I say “small-budget” rather than “indie” because the latter has become more of an aesthetic quality and esoteric vibe than an actual word with meaning). Game trends are entirely genre-driven, from soulslikes to cozy games to the infamous friendslop, and when a game doesn’t have a marketing budget, its success is dependent on its conforming to these trends or, at the very least, to algorithms.

The development of tailored algorithmic feeds has marked the death of the Internet as a place worth visiting, and its consequences reverberate into nearly every facet of modern life. Social media is designed to keep you scrolling for as long as possible by serving you content it thinks will interest you based on your engagement history, and game marketing works the same way. Steam, the largest gaming platform in the world, features a personalized Discovery Queue that presents you with games within your previously played genres in the hopes of predicting your next purchase. This cultural expectation of instant gratification is antithetical to art itself and actively prevents players from encountering meaningful experiences outside of arbitrary genre definitions.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-