Gunpoint (PC)

Tom Francis’ Gunpoint is a game with style. It boasts a thoughtful wit and a strong vibe and a fully-formed sense of self not always found in games from first-time designers. And yet it struggles to stick with me after I’m done playing.

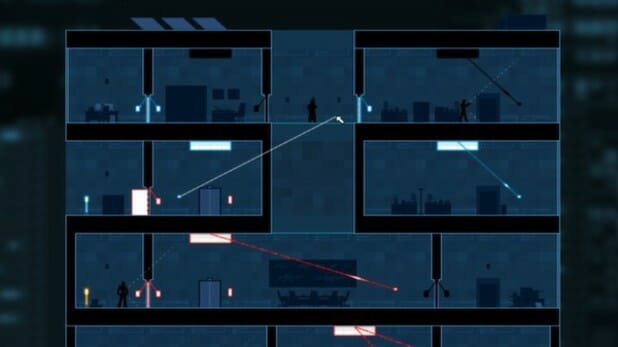

It’s a game of triggers and cause-effect relationships. You spend the game infiltrating various buildings in order to steal plot-relevant data, which translates to getting to a certain part of the level without triggering guards, and finding your way out. You can switch between two visual modes: the “crosslink” mode that allows you to see interactive objects in the space but restricts movement, and its “normal” state, where it’s essentially a stealth platformer.

In crosslink, certain objects can be set to trigger others in the level. You can set a light switch to open a door, or set an elevator to trigger a light that will provoke a guard to start moving, which would allow you to knock him out from behind. When you’re not using crosslink, you can jump high distances and crawl on walls with suction cups and a spring contraption tied to your feet. Apart from being kind of exhilarating to jump across buildings, it’s one of the ways that Gunpoint encourages you to think about its systems in a nuanced, expansive way. Crosslink pushes you to trace intricate cause-effect relationships between objects in the environment. And wall climbing, coupled with multiple passageways, allows you to think through the environment through numerous visual perspectives. Gunpoint’s strength, then, lies in the cycle between analysis and execution: taking the time to really understand a level, then attempting to execute objectives without getting shot or making too much noise. Maneuvering through levels is exciting because it validates your understanding of them, and allows you to see how objects and spaces are connected in real time. When you die in Gunpoint, you have the option of going back in time a set number of seconds before, perhaps 5 seconds or 30 seconds. Every object triggers consistently, and guards are completely predictive. The game ends up feeling like running a simulation you’re inside of.

Gunpoint is similar to Sworcery in that characters aren’t very detailed, but move smoothly, with a convincing weight to their frames. Meanwhile, inanimate background objects like police cars or signage appear less pixelated and more detailed, creating an attractive contrast. Its colors are soft and generally desaturated which corresponds to the game’s overall tone, but can feel dull at times.

The same is true of its music. Levels are played on slow-tempo jazz, the tapping of hi-hats directing melodies played on sax and upright bass. Its moodier tracks can bring an effective tonal frame to the game—composer Francisco Cerda’s menu track for example is phenomenal, and totally sells the mood—but its duller ones kind of drift into the background. It doesn’t help that the same tracks will play in multiple levels consecutively; it doesn’t seem there was much thought put into how tracks would be spread out across the game.

Gunpoint’s play experience is strong, but it’s framed through weak storytelling. You play as Richard Conway, a freelance detective who is framed for the murder of a weapons associate, and you spend the game weaving through secrets and conspiracies to clear your name and find the true killer. Its plot is told between play sessions, in the form of texts between Conway and his various clients. It opens avenues towards interesting conversations, but the story is often told through what feels like text dumps of he-said-she-did, drone-like contextual filler meant to drag us along.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-