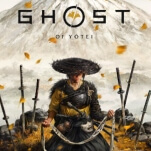

Hornet Makes Silksong Sing

A Relatable Heroine Is the Best Thing about the Hollow Knight Sequel

The first big thing I noticed about Hollow Knight: Silksong is that Hornet has a voice. Just like when you fight against her in the first Hollow Knight, Hornet cries out every time she jumps and flings her body around, so it shouldn’t have surprised me—but there’s a big difference between hearing a boss’ exclamations at you, versus hearing your own player character’s voice. These little voice acting flourishes are called “efforts,” and in the case of Silksong, you can turn them off, if you’re too used to the silent protagonist of the original Hollow Knight. As for me, though, I immediately loved this change, which—if you’ll allow me to be corny—emphasizes the effort behind Hornet’s efforts. This game is brutally difficult, set in a place with a cruel and unforgiving religious culture, and through her voice acting, Hornet is feeling the pain of eking out progress right along with the player, through every jump and dash and swing of her needle.

More importantly, though, Hornet has a voice in the sense that she has actual lines of dialogue, and further vocal flourishes to go with them. In the worlds of Hollow Knight and Hollow Knight: Silksong, all of the little bug enemies do not speak human language. They speak in strange, singsong syllables, sometimes even humming specific and recognizable melodies that allow Hornet (and, in the first game, the Hollow Knight) to more easily find and re-find specific characters by sound alone while exploring huge, labyrinthine areas. Hollow Knight and Silksong also both use subtitles so as to allow the player to actually understand what the bugs are saying, and in Hornet’s case, she says quite a lot.

After many, many hours of Hollow Knight, I was used to the Hollow Knight heading up to various NPCs to hear their stories and their reflections on the protagonist’s strange nature. But the Hollow Knight could never respond; it is a silent protagonist, even within the canon of the game’s world. It is a literal hollow knight, an empty vessel propelled forward by an unseen force. To be clear, I did like this conceit. It almost implies a sense that Hollow Knight’s fourth wall has cracked slightly, because of course the unseen hand controlling the Hollow Knight’s every move is the hand of the player. The player cannot speak to any of these bugs, either, and can only listen and observe the world in silence.

Games with silent protagonists are not always written in such a way as to render the protagonist actually silent. In The Legend of Zelda games, for example, even though the player never learns what Link is saying to other characters, it’s usually clear from their responses that he said something (although, of course, it is funny to imagine that he’s just standing there like the sweet himbo he is). But in Hollow Knight, it’s very clear that the knight cannot talk, and that this is one of the character’s defining traits. In theory, with a silent protagonist, it’s easier for the player to project themselves and their own feelings onto the character, further immersing themselves in the game’s world. And as a huge fan of Metroid games, which almost always have a silent (or at least laconic) heroine, I find it easy to put myself in Samus’ shoes; the concept can really work.

It’s entirely possible that a more Samus-like, reticent Hornet could have worked well in Silksong, and it’s frankly what I expected from the game. I know she talks in the first Hollow Knight, but not much, and with her whole “tough gal” persona, I just didn’t expect her to be doing much more talking in Silksong beyond the bare necessities. Instead, Hornet talks constantly in Silksong, sharing her opinions openly with every NPC she meets, and indeed having an entire emotional arc of her own as she learns and discovers more about the world around her. I didn’t realize how much it was going to change the way that it felt to play a Hollow Knight game—and, in my view, the change significantly improves its storytelling and emotional pull.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-