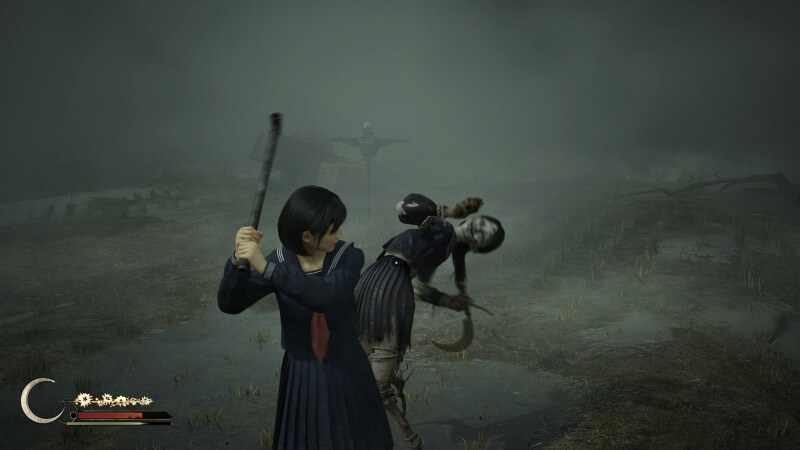

Is It Accurate to Call Silent Hill f a “Soulslike”?

Since Dark Souls altered the entire video game market in 2011, referring to something as “like Dark Souls” has become a foundational cliché of games criticism. As the genre has become further entrenched as a mainstream staple (encoded with the clumsy nomenclature Soulslike), this tendency has now hardened. It’s been used to describe games as diverse as Jedi: Fallen Order, Hollow Knight, and now Silent Hill f. Reviews from GameSpot, TheGamer, and IGN make at least passing mentions of “soulslikes” and the term has shaped more casual discussions of the game. Fundamentally, this shorthand relies on a slight and shallow idea of what a “soulslike” is and an urge to generalize how Silent Hill f works (and how it makes meaning) in detail. In fairness, more than a few reviews disregard the comparison or don’t mention it at all. But no reviews I’ve read dig into the comparison, exploring its validity or even just where it comes from. So let’s be specific and clinical. In what ways does Silent Hill f resembles a soulslike? How it is different? And if it isn’t a soulslike, what it is?

Several hallmarks of the soulslike can be found in Silent Hill f. Protagonist Hinako can attack in two ways, light and heavy, mapped by default to the right bumber and trigger respectively. You can’t cancel attacks if you realize you’ve made a mistake; every button press locks you into an animation. Attacking, dodging, and running take chunks out of a stamina bar, and if you run out, you’ll have to wait until it charges before you can act again. The world is dotted with shrines, where you can spend currency to improve your stats and sell items. And hitting a button at the right time during an enemy’s attack can result in an ultra-effective attack.

Silent Hill f diverges from the soulslike formula in several crucial ways, though. The game autosaves frequently; you will not always be teleported back to the shrines upon death. Enemies don’t drop currency or items when you kill them. You don’t lose anything when you die except forward progress. Defeated enemies don’t respawn when you rest at a checkpoint. There is no “default” healing item which you can upgrade, and you must find all healing items out in the world. You need an additional item to upgrade your stats, as the main currency is not enough on its own. Your inventory is limited, and you cannot carry everything all at once. And weapons degrade with every attack, eventually breaking.

It’s safe to say, given these points, that the comparison doesn’t come from nowhere. You can even frame Dark Souls and Silent Hill as having a shared linage. From Software’s oeuvre since Demon’s Souls has always had horror elements. The games rely on some level of resource management. In both survival horror and From’s action RPGs, enemies are powerful and combat should sometimes be avoided. However, this eludes a fundamental difference between the two designs: in Dark Souls, you are meant to feel powerful.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-