Trine 2 (Multi-Platform)

Trine 2’s December release sets it in-between two epic open-world games, the single-player Skyrim and the massively multi-player Star Wars: The Old Republic. It’s a timing coincidence, of course, but it’s a coincidence that highlights what makes Trine 2 impressive: it’s refreshingly and delightfully small in scale.

Like the original Trine, Trine 2 is a fantasy side-scrolling game where you control a wizard, a thief, and a knight on a fairy tale-like quest to save a kingdom. Each character has different skills that are used to solve puzzles and defeat goblins along the way. The wizard can create boxes and levitate items, the knight is best in combat, and the thief can grapple and swing from wooden objects. The game is also completely linear, as you travel from left to right through a series of levels, solving increasingly difficult puzzles on each screen.

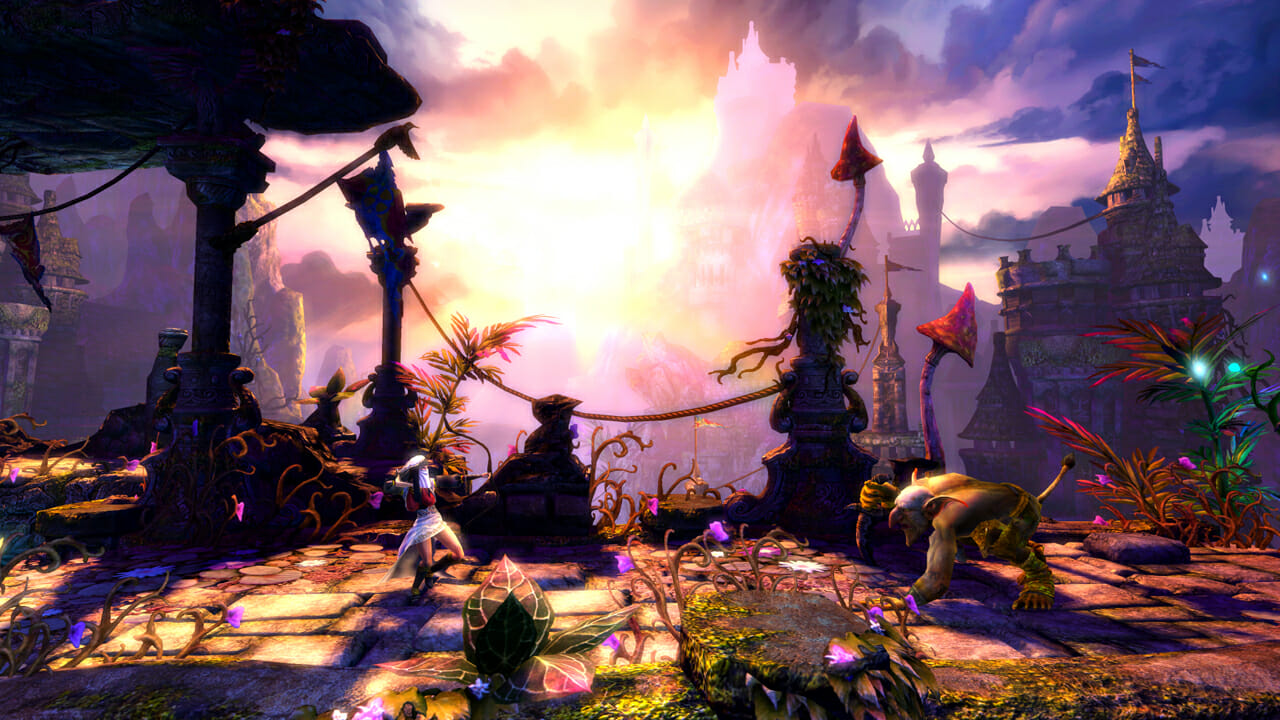

Trine 2 uses its linearity to the best possible effect. Aesthetically, every section of the game feels crafted to be as beautiful as it possibly can, using an overwhelming barrage of colored, glowing lights and clever animation. It’s over-the-top, and it walks a fine line between “charming fantasy” and “Lisa Frank kitsch”, but at times it is stunning that a so-called “indie” game can look this good.

Despite its intentional crafting and linearity Trine 2 actually offers a remarkable amount of freedom, thanks largely to having a core game engine that allows for experimentation with different solutions. Its key component is its physics, which creates grey areas in puzzle-solving. You might encounter a drawbridge attached to a pulley as a counterweight. A simpler game might force you to have the wizard create a box and drop it on the counterweight platform, which would be one option in Trine 2, but there are always others. If the wizard has had his skills improved, he can maybe make multiple boxes and simply climb those. Or he can use his levitation power on the pulley more directly. Or the thief can grapple the pulley, using her weight to pull it down, and swing across.

This flexibility isn’t just a pleasant side-effect of a well-developed physics engine, it’s also necessary for the game’s multi-player component. In single-player, you control one character at a time, alternating between each on the fly. In multi-player, each character is controlled by a different player, meaning that a chasm that’s easy for the thief to cross will require a different set of skills for the wizard or the knight, and may require more coordination.

In many puzzle games, you get the feeling that you’re competing with the puzzle designers, who created a single solution that you have to work to find. If you’re not thinking in exactly the right way, it can be frustrating. Trine 2 offers multiple player-driven solutions so that each one feels unique. It’s not a competition with an unknown designer’s ideal solution. Instead, it’s a competition between you and the game’s environment. This gives puzzle completion a different form of validation, a personal feeling of success thanks to intelligence and skill, instead of simply conquering a design.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-