Volume: Warm Blood in a Mechanical Body

Stealth games can feel pretty artificial. Though the genre is meant to simulate the sort of behavior a real person might exhibit—investigating a strange noise off in the distance, ignoring a barely noticeable shape in a room’s periphery—turning these actions into game mechanics requires rigid systems. Stick too close to reality and a player will be hunted across entire levels by guards who refuse to shrug their shoulders and return to their posts after spotting an intruder. Model natural bodily ticks, like glancing over a shoulder, and the action becomes too unpredictable. To make videogame stealth enjoyable, it’s necessary to codify human behavior—to render the erratic with a computer’s logic.

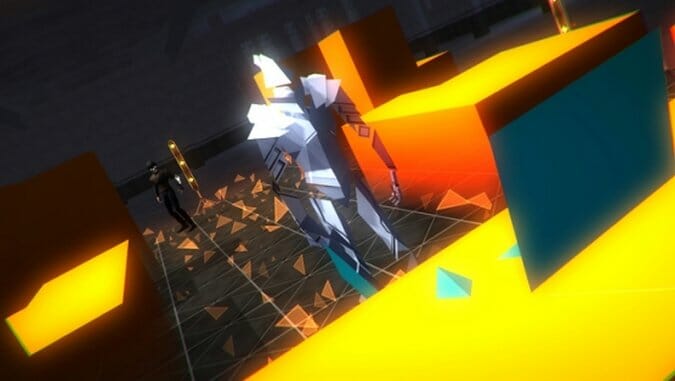

Bithell Games’ Volume is about this struggle. Its attempt to merge the organic and artificial shapes not only the game’s aesthetic, but its storyline and mechanical design, too. This isn’t a new concern for Bithell. His previous game, Thomas Was Alone, developed a cast of emotionally-driven characters out of puzzle-solving artificial intelligences drawn as utilitarian geometric shapes. Volume goes a step further, setting itself in a dystopic England where technology and unchecked corporatism have exerted a stranglehold on humanity. In its world, people have been subjugated, pressed under the thumb of a totalitarian government’s technocratic order.

Protagonist Robert Locksley puts the plot in motion by subverting this, breaking into a military training center—dubbed a Volume—capable of turning a warehouse into a virtual representation of nearly any environment. After hijacking the Volume’s AI, Locksley begins running through digitized versions of the homes and offices of England’s corporate elite. By broadcasting himself sneaking around, outwitting guards, and grabbing floating gems meant to represent the upper classes’ money and secrets, Locksley hopes to inspire viewers to follow suit in the real world. He wants to provoke a people’s revolution by reversing his government’s means of control.

The story is meant to play as a kind of cyberpunk update of the Robin Hood legend, reworked for an era where the oppression of an aristocratic Sherriff of Nottingham is more suitably represented by a law manipulating business like Volume’s Gisborne Industries. What’s most striking about the game, though, isn’t its well presented yet fairly familiar take on corporate greed, but its decision to represent the underdog potentialities of the internet as the Sherwood Forest its heroes strike from.

As Locksley gains a fan following by successfully stealing from simulacrums of Gisborne associates’ homes—conveyed as a neatly segmented series of 100 levels—his popularity escalates in proportion to the danger he places himself in. Viewers from across poverty-ridden future England tune in to watch as Locksley shows just how possible it is for people like him to overthrow the system they seem bound to.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-