Our Love-Hate Relationship with Silksong‘s Compass

I am terrible with navigation, both in video games and in real life. When I get lost in real life, I do end up fine, thanks to the aid of my smartphone—except for that one time I was driving home in an unfamiliar place, my phone ran out of battery, and the phone charger in my car wasn’t working. I wish I could say I relied on street signs and the ancient paper maps in my glovebox to get back home, but that wouldn’t be true. Instead I just kept plugging the charger back in until it finally started working again. In video games as well, I cling onto mapping tools for dear life.

I’m not proud of this. I have many friends who turn off mapping and guidance tools in video games for the sake of “immersion,” and I feel some envy at their ability to navigate using their own innate sense of direction. Their screenshots look so great without all that clutter on the screen. I’m sure they’re better at appreciating the environmental design of various games that emphasize exploration and discovery, too. For me, that’s never gonna work. I need all of the guidance I can get, or else I’m going to be walking in a circle for far longer than I care to admit publicly. The fact that Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 didn’t have individual level maps was a huge issue for me, and I can promise you that I could have completed that game a lot faster if it had included maps.

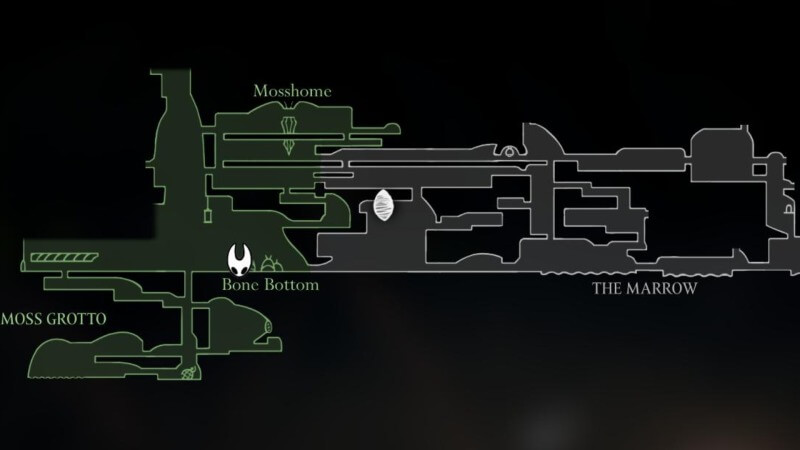

This is also one of my only serious complaints about Hollow Knight: Silksong and its predecessor, Hollow Knight. The games both have a means by which the protagonist can equip a very limited number of items into certain slots, and there’s an item called the Compass in both games that I have had to keep equipped 100% of the time. It takes up precious space, especially given how limited these item slots are, but I can’t unequip it. I know, because I’ve tried, and I immediately get lost when I do.

To explain why, I need to explain how maps work in these games. The protagonists of Hollow Knight and Hollow Knight: Silksong both get access to maps by running into a specific NPC in each new area of the game and obtaining a new map from them. That’s fine with me; it makes sense, and it’s adorable that in both games, you get to see a little animation of the protagonist literally holding up the map whenever the player clicks the button to look at it. The game doesn’t “pause” while you look at the map, so you have to do it when you’re in a safe spot. All of that is delightful, and I’m very glad it’s there. The NPCs who sell the maps are some of my favorite characters in both games, too, because they both add a lot of flavor and color to the world.

So, if you’ve never played these games, you’re probably wondering how, if I have access to a map, I’m managing to get lost without using this other tool called the Compass. That’s because the Compass tool is the only way that you can tell where your character is on the map. Obviously, on a real-life paper map that you carry around with you, there would be no magical “You Are Here” sticker that moves around along with you. Because the characters in Hollow Knight and Silksong are visibly carrying around actual paper maps, it makes sense that they need to use their own brains to figure out where they are, or instead use the magical Compass tool to see themselves on the map. This is part of why I feel bad complaining about it; I understand it.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-