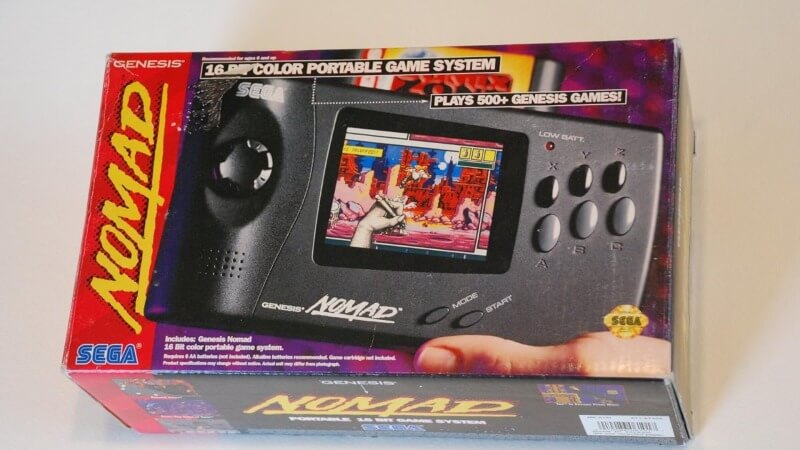

30 Years Ago the Genesis Hit the Road with the Sega Nomad

In the mid-1990s, Sega went to significant lengths to extend the life of their 16-bit Sega Genesis any way that they could. There was the Sega CD add-on, which allowed for enhanced Red Book audio, and offered loads of space for visuals, scripts or other extras that couldn’t fit on the smaller storage size of a cartridge. There was the 32X, a 32-bit add-on which in North America was meant to serve as either a bridge to or replacement for Sega of Japan’s plans with the Sega Saturn, but that, with a library of 40 games and just 800,000 units sold, ended up being neither of those things.

Far less discussed than those pieces that let you turn your Genesis into a little multi-part tower was the Sega Nomad. While Sega’s 8-bit portable competitor to Nintendo’s Game Boy, the Game Gear, could play Master System games with an adapter, the Nomad natively played Genesis carts. In fact, that was its entire purpose: it didn’t have its own library of Nomad exclusives, but was meant to be a portable Genesis. The other name the handheld is known by is the “Genesis Nomad,” even.

It was a North American-exclusive handheld, based on a Japanese Sega product known as the Mega Jet. The Mega Jet was a portable Genesis—well, Mega Drive, since this is Japan—named such as it was hooked up to a screen during Japan Airline flights, but could also be used in a car that happened to have a TV screen and cigarette lighter to plug into. Sega of America took that concept and added a screen, removed the need for plugging it into a power source by adding batteries, but kept the ability to plug the system into a TV so you could play games on a larger screen if you had one available.

Pretty amazing, right? A few things happened that kept it from catching on. It was released in October of 1995, well into the existence of the Genesis—that was great news as far as an existing library goes, as it was hundreds and hundreds of games at this point. However, it was also five months after the launch of the Saturn in North America and a month after Sony’s Playstation arrived there: the former was a focal point for Sega internationally, while the latter was also consuming Sega’s attention in a very different way.

In addition, it hit the market for $179—for comparison’s sake, the Game Boy launched in 1989 at $90 and the Game Gear in 1991 at $150. It never fully took off, though. Over the course of four years, just one million Nomads were sold. The price probably played a little bit of a role in that, but there also weren’t new games being released just for it, as Sega as a whole was slowing down releases for the Genesis much more quickly than Nintendo did with the SNES.

The price came from the expensive technology inside of it: the 3.25-inch, backlit LCD screen was meant to overshadow Nintendo’s monochrome and aging Game Boy, just like going with a full color display on the Game Gear was supposed to, only this time for 16-bit games that you already owned. So there was an upfront cost, but, again like with the Game Gear, a secondary one as well: you needed a lot of batteries to make the Nomad work. So many batteries. You could get around three to four hours of battery life for your Nomad from six AA batteries from the higher-end estimates out there, and fewer than three from the lower ones—this thing could be portable, but plugging it into the wall through an AC adapter was the best way to keep it going. That limited—though did not entirely get rid of—its portable nature. But the fact the Game Boy could run for over 10 hours on just four AA batteries was a major advantage before you even get into how it cost half as much as the Nomad.

Sega and Nintendo were basically opposites in the handheld space. Sega had the same mentality that they did everywhere else, which is to say that power and speed could solve just about anything—that’s not to say that their games were all flash and no substance, by any means, but as far as hardware goes, they really wanted to be able to have flash, too. Nintendo, on the other hand, designed the Game Boy using Gunpei Yokoi’s philosophy of “lateral thinking with withered technology,” which is to say an emphasis on cheaper, mature technologies. The Game Boy—which was designed by Yokoi as well as Satoru Okada—was behind, technologically speaking, in comparison to the Game Gear or the Atari Lynx, but it cost a whole lot less to make and for customers to buy: again, the Game Boy was $90 and came with Tetris in North America, while the Game Gear cost $150 and lacked a pack-in title. Tetris and fewer times having to beg your parents for batteries? A choice made easy.

When the Nomad arrived, however, Game Boy sales had been flagging. It had already been using old hardware when it had launched six years prior, and it wasn’t any newer in ‘95. The CEO of Sega of America, Tom Kalinske, had big dreams for replacing the Game Gear with something much more powerful and more expensive, but that could pull people away from the Game Boy at this moment when its grip on the market had loosened. Via IGN:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-